In 2017, Simon Moreton’s father fell suddenly ill and died. His death sent the author back to his childhood home in rural Shropshire trying to process his grief by revisiting his family’s time as transplants to the countryside. Combining prose, illustration, photos, archival texts, and more, Simon’s memoir ‘WHERE?’ is just-published by Little Toller. Read an extract from the book below.

Caynham sits about three miles down the hill from Titterstone Clee. Although the parish of the same name is a widely distributed series of farms and hamlets and small housing estates across Clee and its southwestern slopes, the village itself is tiny. It is strung along the lower reaches of the road to the hill, clustering around a church (twelfth century), a village hall (twentieth century) and a now-closed school (nineteenth century), all under the watchful promontory of Caynham Camp, a hill fort (c. eighth century BC).

We lived in a newly built house at the bottom of a little incline, tucked off the main road between Ludlow and Clee. Ours was one of a couple of dozen houses built around the diminishing activities of a commercial turkey farm and the remnants of an empty stately home, Caynham Court. We lived next door to the remains of its walled gardens which were full of rubble and dock. We called it ‘the dump’.

I went to school first in nearby Ludlow – Sandpits, Clee View, got bullied; tough class, tough kids, tough lives, forgotten families out in the fields and the estates – before changing school to the village school, country kids, a different pace, sheep in the school field.

In the general vicinity of where we lived there were a lot of woods, fields and farms. It was very quiet – quieter than suburban Surrey where we’d lived before (darker, too – no streetlights), except when the birds sang and the sun came up and it was as loud and bright as any town.

Next to the Court there was an old saggy caravan that sat like a chest with its ribs showing. I can still see it clearly. My brother struggles to recall this, but once we tried to use Blu Tack as an explosive in the caravan’s padlock, because it looked like something we’d seen on TV, but of course we didn’t have any matches and Blu Tack isn’t an explosive.

We did eventually get inside when the fibreglass and plywood gave in like wet cardboard and the door buckled, revealing a damp, rotten lung. I don’t remember what was inside: papers, a coffee cup overflowing with mould, mud, gold, a murder victim, or maybe nothing.

Caynham Court itself sat abandoned and boarded up behind our house. It grew out of the rubble and grass and brambles like a brick plant. It had past lives – a Jacobean manor house, come and gone; an eighteenth-century stately home; a wartime evacuation for the Lancing College private school, boys living and being taught while the war came across the sea; later, Hillhampton House for girls, Miss Liesching teaching home economics and household skills; then, later still, offices for a turkey hatchery, then vacant.

It was a concrete time machine. You could smell its spores and dampness and cold, undisturbed air through cracks in the brickwork. There were glimpses to be had of the interior; there was a toilet block with its rear wall demolished, exposing the porcelain to the elements, but with the door connecting to the main building sealed off; from the locked patio doors, glass still intact, you could see directly through a drawing room, to a bookshelf which miraculously still heaved with books.

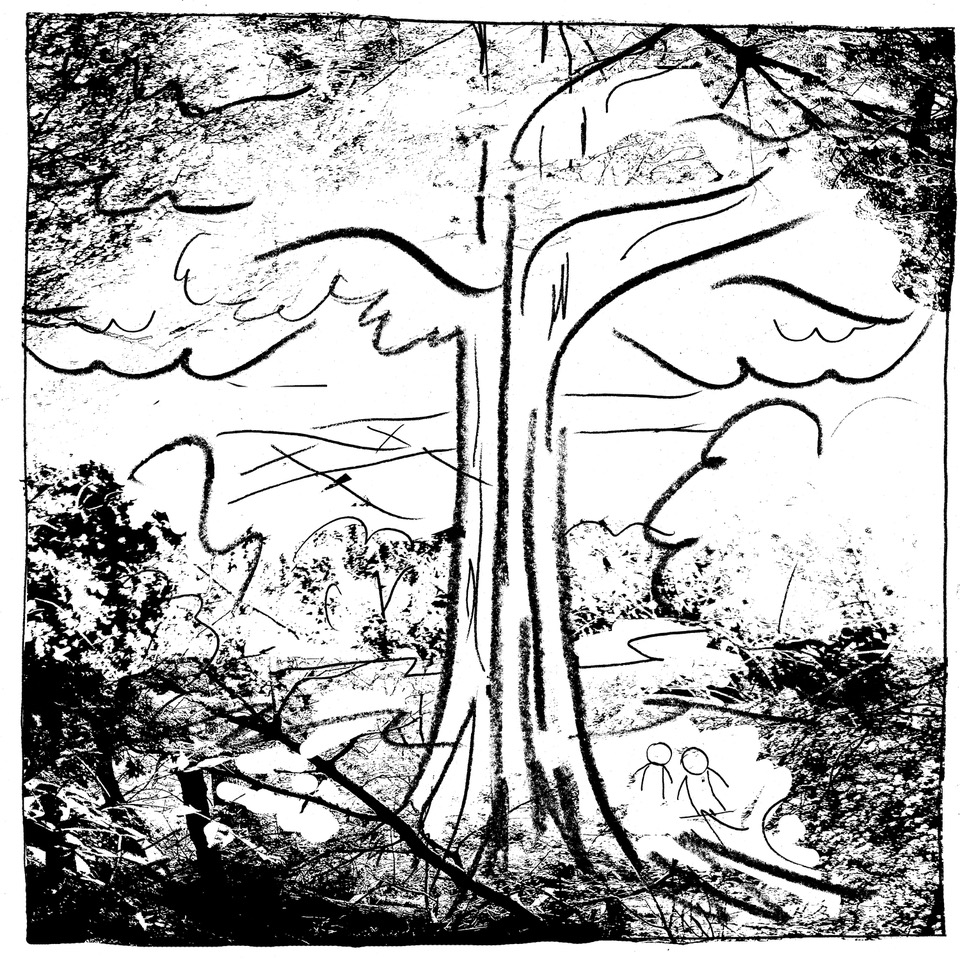

Caynham Court at its peak presided over five hundred acres of parkland and walled gardens, mounted on a haha tipping away to the Ledwyche Brook which flowed south past the estate. There were also kennels, farmland, stables and a mill. The County Seats Of Shropshire: A Series Of Descriptive Sketches, With Historical And Antiquarian Notes, Of The Principal Family Mansions contains a pencil sketch of the Court, looking out west from the tree-line of the neighbouring woodland, across a landscaped moat. The curdled remains of the crossing point, a decorative iron bridge, were still present when Tim and I would sneak into those woods. The bridge looked like a tangled, rusty climbing frame. We’d slide down the ditch bank, through our neighbours’ grass clippings and bin bags. Then we’d explore. First the flowing water of the Ledwyche, then the plantations of trees, incongruous bamboos amongst birches and flowering nettles. Then, with our backs to the brook, and facing up the hill, we’d seek out the redwood, whose crown you could see from our house, and touch its papery, coconut-husk bark. We built dens. My cousin Ewan did a poo behind a bush up there.

Here, life crawled like a dream. I’d lie in bed in the mornings, awake at sunrise, long grey curtains over sash windows. Sometimes I’d creep across my room to wave at the bin men, and they’d wave back. In the cold grey paper dawn I’d listen to the wood pigeons. I knew, very particularly, that they were doctors of some sort. I didn’t know their motives, but I was convinced they were up to something sinister, hoo-hoo-hooing across the dump from the woods.

A slate roof amplified the rain noise. The Great Storm of 1987 took a tile and threw it, corner down, into the front lawn so it looked like a standing stone. One autumn the leatherjackets came out like a mini-plague, undulating through the grass and across the paving slabs of the garden path, while in the summer, life on the patio was red mites the colour of a word processor spelling error.

In the back garden the earth was wet, there was the smell of grass, in the spring morning, in the winter wind, in the March frost or under the brown humus sluice of autumn. We climbed the walnut tree that grew there, our own little river flowing from the sky. There were streams of white bark, and small, black knots tarred shut, like rocks in the rapids. The leaves were its banks, full in June, spare in December. We canoed up and down, learning the nooks and pools of each crook, and the best places to sit and dangle our feet. I never got stuck, and I never fell out.

We’d play on the back lawn in the summer until a storm turned silent jaundiced skies into black clouds and the tension would yield and we’d run around, picking up our toys in a bid to get inside, darting between the giant raindrops before there were no gaps of dry air left to occupy; in the garage, Dad taught us to make things out of wood, and cooked whitebait on a camping stove.

It was living here that I fell in love with the natural world. Everything was connected, wild, confusing, terrifying and comforting. I didn’t think of what people did as being separate from what the birds and the beasts did. Homes popped out of the ground like shrubs. People planted fences in the same way that the maroon docks seeded themselves in piles of builders’ waste. The earth birthed blue and white crockery pieces, while berries grew on barbed wire, and television aerials throbbed with incoming cartoon energy. I came to know – without even realising it – the smell of thousands of years of stratifying, rolling earth, of sheep wool and cow shit and clay soil and rotting leaves, and the bright voltage of water.

I watched the purple plummish damsons ripen in the hedge opposite our house, plump like wrens. They hung by a gap in the foliage that dropped to a wonky plank of wood, pitched over a squelch of a ditch. I’d walk to the village school over that improvised bridge, up the small bank on the other side, over the fence and into the school field.

I read fantasy paperbacks containing things I understood and things I didn’t, but which I loved unconditionally – swords and landscapes, all of that, and the cover art – oh my, the covers!

I learned about the vegetable patch with its potatoes, clay pipes and slug traps full of home-brewed beer; about the mysteries of the garage, with its tea chests and garden toys, Dad’s white cupboard with boxes of capacitors and screws; about the green oil tank behind the little bit of fence, with the plunge button you’d press to see how much oil was available; and about how the hornbeam Dad planted grew, and why he’d have his photo taken next to it every year.

I danced around to ‘Smooth Criminal’ in my bedroom, but didn’t understand that Michael Jackson had multi-tracked his voice on his recordings (it took me years – and I mean years – to work that out). I just thought all of his backing singers sounded exactly like him.

I learned to swim but wouldn’t put my head under the water. I learned what a horse sounded like when it farted, and how not to be scared of cows.

Before I moved to the village school, I was a quiet child. While other children – alluring, unpredictable and unknowable – paired off like swans, roamed in packs, floated around like seeds on the wind, or fought like dust storms, I worked through various fixations: with birds and trees, with Michael Jackson, the animal kingdom, dinosaurs, astronomy, orcs, goblins, wizards and hobbits. I was bemused by my classmates at school in Ludlow who accused me of reading the encyclopaedia for fun as if that was a bad thing. Of course I did. Who wouldn’t?

I stuck my face in books about magic and about animals and animal tracks and I didn’t know about sport as practice, nor sport as a culture; I tended to catch balls designed for my hands with my face, and balls designed for my feet with my hands. I remember how heavy the football was when I tried to kick it in my oversized studded boots during PE lessons in the muddy field. I was small for my age and my ankles were pampas.

I didn’t know the language of bodies and clothes and names and numbers and stadium locations. I was more interested in the walnuts from the tree, marvelling at the black stains of their desiccating skins, monitoring them as they dried on the rack propped up by bricks at the side of the house, or watching them pickle in jars at the back of the cupboard, like little woody cortexes bobbing around in ink.

I did not know ‘teams’ and when I started at the village school, all the boys liked Liverpool FC. ‘Who do you support?’ they asked on my first day. I didn’t even understand the question, so there wasn’t any time to make up a lie. I had never grown up thinking that not knowing about football or rugby or racing or horses or cricket was a bad thing. Thankfully, neither did these boys. They weren’t like the other boys I had met by that point in my life; they just shrugged and tried to teach me to play football.

I sometimes think it would be nice to go back and feel like that again, and sometimes I am glad I never can.

*

‘WHERE?’ is out now and available here (£20.00).

You can follow Simon on Twitter here.