John Andrews casts an admiring eye over Luke Stephenson’s latest photo-book; a document of the UK’s most popular participation sport.

Not since Hall & Co. merged with Ready Mixed Concrete Limited in 1971 and published its Leisure Sport Handbook has there been such a striking piece of angling publishing as British Record Fish by Luke Stephenson (Stephenson Press). Appropriately, the two works share a similar design, both having landscape covers rendered in brilliant orange. But where the Leisure Sport Handbook of 71-72 is ring bound in cardboard, British Record Fish is perfect bound in plastic, giving it the appearance of a giant-sized angling permit; fitting perhaps, given that its contents are a presentation of thirty-one British Record Fish from the The British Record (rod-caught) Fish Committee, with accompanying landscape photography by the author.

In holding this ‘giant permit’ — this season-ticket to greatness — one is struck by the fact that many an angler who took possession of a Leisure Sport Permit in 1971 did so with the dream of breaking a British Record on waters that would go on to become hallowed names in angling such as Yateley, Wraysbury and Darenth. But records aren’t broken by design and in angling, more than in any other sport, they are broken as much by chance and luck. And this is in a world where spiking of baits with additives and proteins is positively encouraged — to the point that it has spawned a huge industry in processed bait — and in a world where tackle has been refined to the point where electronics are employed to locate leviathans in the cross-hairs of desire.

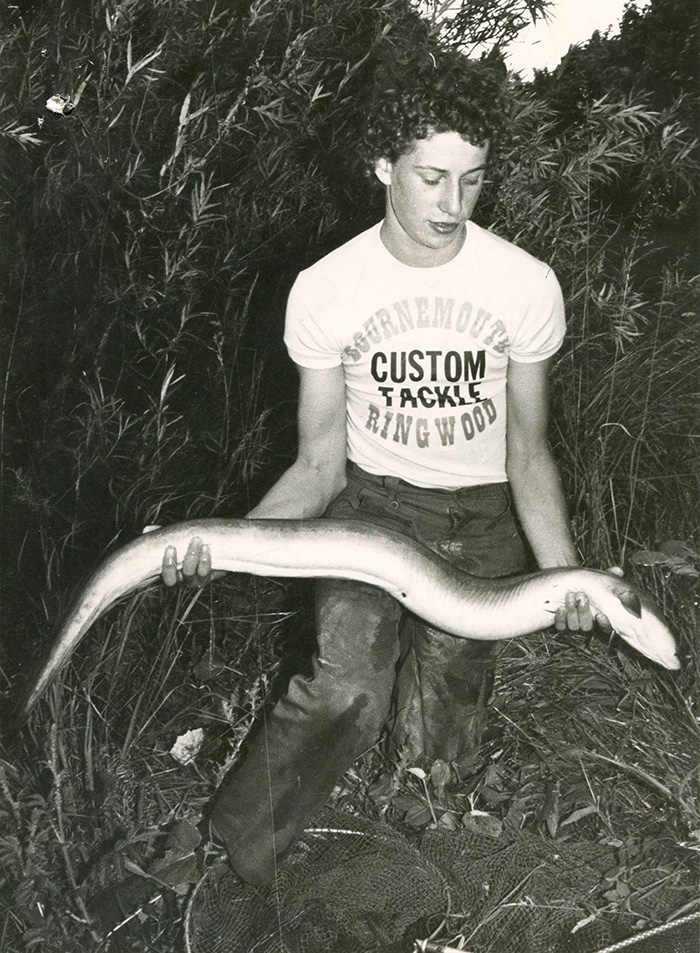

Whilst it is true that there are some fish in Stephenson’s book which you might argue were consciously pursued, such as the 21lb 1oz barbel taken from Adams Mill in Bucks, or the 4lbs 10oz crucian carp taken from Johnson’s Lake at Marsh Farm in Surrey, there are also enough unexpected monsters nestling between its covers to remind the reader that at its best angling is about myth made real. Who can forget Stephen Terry’s record eel, which tipped the scales at 11lbs 2oz in 1979 and lives on in the imagination of a generation night-fishers? A catch of such astonishing size that one knew as soon as one heard of it that it would never be equalled or surpassed, the photographs of which created a cult fashion for the Bournemouth/Ringwood Custom Tackle yellow t-shirt in which Terry was photographed cradling his improbable anguilla.

The record common bream appears on Page 3, a 22lbs 11oz dustbin lid that was caught accidentally whilst its captor was carp fishing at Ferry Lagoon in Cambridgeshire. This was no boilie-pumped fen-dweller, but the product of a water so fertile that its marine life had transformed it into an electric soup of micronutrients on which huge shoals of outsized bream gorged like whales. This was another fish, like Terry’s, that came in the night; an apparition in the equivalent of angling’s room at the top, transporting its captor into a unique realm of consciousness — just as in the fable of Jack Hilton, who upon seeing the largest carp believed to have swum in Redmire, gave up his job as a plasterer, packed up his Alan Brown rods and took to the road as a Jehovah’s Witness, saying privately to his longstanding angling pal Bill Quinlan that on that afternoon when the head of ‘the’ fish had appeared at one end of a weed bed and the tail at the other that what he had seen was not a carp but the face of God himself. Each of the captors in Stephenson’s book have had such an encounter; each of them have had an adrenaline rush that could have stopped their heart in an instant.

Stephenson’s genius is that he does not bore us with the account of the capture, or the detail of the bait, or the direction of the wind, or whether it was the captors’ fourtieth night that season spent in the sweaty confines of an old army sleeping bag hidden away in a bivvy in the corner of the lake where only rats dwell. The genius is that years on from the capture of each of the records, Stephenson travels to the water and photographs each with the cold eye of someone recording an historic crime scene. These he juxtapositions next to the official portrait of angler and fish. The portraits are familiar (most anglers will remember seeing them at some point in the distant past, plastered across the front of the angling weeklies) but it is the location photographs that are more beguiling. Stare at them for a while and you find yourself searching for the face of God, for a tell-tale sign, like a crying statue of Our Lady hidden by reeds, or a shaft of sunlight breaking momentarily on the water. But in each one there is no revelation: merely a vast emptiness, a soul crater left behind by the one-off explosion that occurred when the impossible happened and a British Record Fish was taken from an otherwise run-of-the-mill pond or stream.

Stephenson’s work is a delight which sits well with 99 x 99s — his photographic project which documented the story of the 99 ice cream through a road trip around the UK, and in all its spooky charm recalls Bob Moss’ Through a Line Tightly (Bob Moss 2003) — and The Shipping Forecast by Mark Power (Zelda Cheetah Press 1996).

*

‘British Record Fish’ is out now and available here (£25.00).