Every year, we give over all of December (and usually most of January) to a series called ‘Shadows and Reflections’, in which our contributors share highs, lows and oddments from the past 12 months. Today it’s the turn of Emma Warren.

English, Irish…Janner?

I was sitting on the battered Chesterfield sofa at Total Refreshment Centre after an emotional evening at the CHICAGOxLONDON show at the Barbican. The event, which was part of London Jazz Festival, celebrated the ongoing connection between the cities and also recognised the absence of the incredible jaimie branch who was due to have played. I usually go home after gigs these days, but this was different and we all went back to TRC afterwards. The sofa provided the right environment for a conversational cocoon with my friend and co-conspirator Scottie McNeice who runs the superb International Anthem. We hadn’t seen each other since before the pandemic and there was a lot to catch up on. A few hours in he asked me a question that I wasn’t expecting: “I keep meaning to ask you,” he said. “I’m interested in how you connect with your Irishness.”

I became Irish, technically at least, in the summer of 2017. A few weeks after my paperwork came through, I hosted a back yard citizenship celebration with friends and family. My mum and my other mother — my son’s paternal grandmother — had an Irish parent or went to school in Ireland and both lived a large portion of their lives as practicing Catholics. This might explain why they drove over in cobbled-together leprechaun costumes, giggling like children, and half-danced into the back yard singing the otherwise eyebrow-raising If You’re Irish Come into the Parlour.

This year I have deepened my Brexit-acquired citizenship by tuning into radio, music, film and literature, as a kind of auto-enculturation. It’s been a way of swerving the intense difficulty of this moment in time, when England’s support systems are breaking into pieces and when almost everyone is experiencing the same perils that have long faced those on the margins. It was also a way of attempting to do some ambient fact-checking for my new book, which contains a chapter on Irish dancefloors in the 1930s. I’d done a tonne of specific research, but I knew I lacked the bigger picture and therefore wanted to try and soak up some context — just in case it helped me avoid unnecessarily embarrassing myself.

It would of course be a stretch to call myself ‘Anglo-Irish’. My sister’s kids are properly Anglo-Irish with their Dubliner dad, but I’ve only been to Ireland once or twice a decade, most recently visiting my mum’s cousins in Tipperary. I’m one of six million British people with an Irish grandparent — big deal. Droning on about random relatives from Ballycommon or doing what my friend (and author of the forthcoming All The Houses I’ve Ever Lived In) Kieran Yates describes as ‘begging the culture’ can cause significant amounts of eye-rolling. We lack a word in English to describe the feeling of distancing yourself from another person’s attempt to gain proximity through the medium of ancestry. I’ve probably instigated this feeling as well as having experienced it.

Ancestry can be a route into awareness. Until recently I knew only a little more Irish history than most English people, deprived as we are by a school curriculum that still favours Tudors and Stuarts over De Valera and Collins and by a culture that is broadly blind to England’s histories with Ireland. This is of course also true for England’s relationship to the histories of the other countries in the UK — as made clear in Richard King’s brilliant Brittle With Relics — or indeed the broader realities embedded in the phrase ‘Global Britain’.

The context I received came from family. My grandmother Máire told me that her father had been born towards the end of the famine, that his family’s farm had been “taken by the English” and that they’d been brutally evicted. These little pieces of very local history meant that I understood at least something of the human cost of England’s extractive relationship with its nearest neighbour. She spoke some Gaelic and I recall the nudge of separation I experienced when I heard her sharing language with my brother-in-law. Their words and phrases created a bridge between them; one that was inaccessible to the rest of us. I knew more Welsh growing up than Gaelic (my mum taught me how to say lechya da, which for some reason I thought meant ‘give us a kiss’).

Being brought up Roman Catholic and going to Catholic schools, though, created some shared cultural architecture with anyone else who’d dressed up like a tiny bride for their First Holy Communion or who’d made up sins to tell a generic Fr. Phelan at confession because they didn’t have enough real ones. These were minute and disconnected aspects of identity, which — obviously — were categorically different from being Irish. I’m just a southeast Londoner with a higher-than-average proximity to claddagh rings and communion. I wondered about identity regularly this year, something that also allowed me to notice new feelings. For example, feeling slightly aggrieved to discover that my friend, who’d describe herself as being from Kent, had two Irish grandparents — and appeared to have zero interest in getting her name on the Register of Foreign Births.

Having an Irish passport is a huge privilege and I’m aware that not everyone’s family gifted them the same kind of Brexit-parachute, so I apologise to anyone without passport-generating relatives (and to those who’ve had to go through the staged idiocy of the British Citizenship test). I’ve come across several friends this year who’ve been digging into their histories with a view to collecting new passports, whether they’re Jamaican, Ghanaian or Polish. Perhaps this is one of the actual benefits of the Great Brexit Disaster; that more English people are looking outwards, recognising that this small collection of Atlantic islands isn’t the exceptional centre of the universe. I’m aware of the risk of identity as a kind of dressing-up box, not least because some identities are landed upon individuals and can’t be selected like a nice coat, to take on or off — although there’s a parallel universe in which I dig into the question posed by a friend, when I told him that my dad was from Plymouth: “Oh, so you’re half Janner then?”

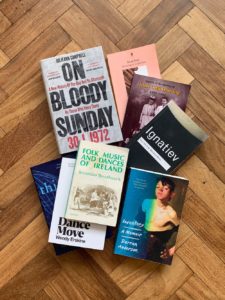

This year I’ve been increasingly drawn to Irish Things. I’ve fallen into a slipstream of literature from Brian Friel’s Translations (thank you, writer friend Nadia Gilani) and Dancing in Lughnasa to reading niche publications on the history of Irish step dancing. I’ve also been reading contemporary Northern Irish writers, from the brilliant Wendy Erskine to Darran Anderson (who I heard talking at Wendy’s book launch at The Social when she generously shared the stage with four other writers) alongside classics, including poet Frank Ormsby and Glenn Patterson’s brilliant Belfast-based novel The International.

In January I started listening regularly to RTÉ radio and the Gaelic-language branch of the national broadcaster, Raidió na Gaeltachta (sidenote: it’s really nice to say these words out loud, especially the last bit with the percussive ‘ta!’ tacked onto the end of ‘gail-tack-ta’). I’d listen to RTÉ a few times a day, just to start getting a sense of the mainstream narrative — like I mentioned earlier, I’d included an Irish-based chapter in my book. This meant becoming acquainted with Ryan Tubridy discussing Rebel Irish Women on his daytime morning show or tuning in as Joe Collins transmitted the sound of weary eyebrows being raised as he half-tried to stop callers talking over each other. Replays of Paddy Gorman’s Paddy’s People documentaries, where he recorded conversations in dole queues and at the bookies, made history real. The Arena culture show led me to Juliann Campbell’s unmissable oral history of Bloody Sunday whilst an interview with a theatre director allowed me to understand the tragic fire at Dublin’s Stardust nightclub in 1981.

I noticed that Irish presenters connected differently with their interviewees, and not just because ‘you’re very welcome’ is an introductory phrase and not a response. There was little of the performative combat, honed in the unreality of the Oxford Student Union, that is common to many English broadcasters. On the downside, I missed the multicultural perspectives, voices and music that is embedded into my usual listening. Cian O’Ciobhain’s nightly music show became a new favourite, reminding me of Andrew Weatherall’s NTS shows — if he were broadcasting in Gaelic from Galway. Cian’s Instagram feed also gave me access to jokes and memes that I’d regularly screenshot for friends and family Whatsapp groups. I couldn’t understand what he was saying so his links became lyrical, or musical perhaps, just giving me the song of language and perhaps a few radio words: phrases that sound like ‘ehr sha’ or ‘holeesh’ appearing regularly before the title of a song or the song itself.

I’ve got a lot from my identity excursions this year, and I’ve a million other books, plays and poems to read, films to watch and radio to listen to. And if in 2023 you see me looking out from Plymouth Hoe, you’ll know why.