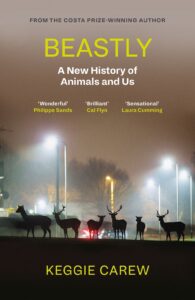

Published earlier this month by Canongate, Keggie Carew’s ‘Beastly: A New History of Animals and Us’ aims to capture the 40,000-year story of animals and humans as it has never been captured before: eye-to-eye and claw-to-hand. Abi Andrews reviews, finding a book which will summon your snorting, snivelling, animal self.

The way we relate to animals is key to understanding the ecological crises of our times — this is the main claim of Keggie Carew’s Beastly: A New History of Animals and Us. We can lock eyes with animals, and they confront us with this call to witness. The relationship? Spoiler: it’s bad. Venatio in the coliseums, zoos, factory farms, animal experiments, trophy hunting: Carew tracks the heavy and perverse ways humans have treated and continue to treat animals.

Like the spectacle of animals led en masse through the desert in the 1800s, to their imprisonment in European zoos — a three month journey from the Red Sea to Hamburg — strung up in a narrow caravan, like some inverted Noah’s ark. Reading this book you become a traitorous human — one who cheers for the wild baboons who respond to the screaming of their captured kin, running down from the hills to attack the human captors — feeling glee at their revenge.

But between accounts of human damage and perversion, it’s the vignettes of solidarity that become emblazoned on the imagination, written with empathy and enrapturement. The other, biophilic people, who cross the supposed human-animal divide, and the animals that meet them in the middle. Magnificent photographs (fox on a woman’s back, boar asleep in a bed and woman curled up on the floor) of the ‘spirits of the book’; a couple who lived in a cabin in Białowieża forest in Poland, with a boar and a raven, in a place where the ‘rules of nature flipped’, into a parallel world of ‘preposterous beauty’.

In its shining passages, Beastly makes no apology for anthropomorphism, and this is the way it should be; the principle of parsimony enacted. ‘When they put their arms around each other as if they are embracing, they are embracing’. Carew’s astonishment is palpable and transferable: ‘What aim, what vision, what dexterity, what a piece of work is a moth.’ But her frustration is also palpable, where she seems pressed to further embellish this astonishment with the services animals provide us. As the book goes on, Carew appears less patient (and rightly so) for any readers who might still be weak in their impulse to recognise animal personhood. ‘The burden of proof was the creatures’ burden’.

Carew reminds us that the Cambridge Declaration which acknowledged animal consciousness was signed in 2012. That scientists have ceased trying to teach animals human language, and prefer to study animals in their own worlds. And yet, in response to a call in the UK for a ban on farrowing crates in pig factory farming, in which a mother pig may only stand up or lie down, the industry responded with bigger crates, where a sow could now turn around, and called them “freedom pens”. This was in 2021. The relationship remains contradictory.

A question, or questions, bugged me in reading Beastly. Who is the “we” that Carew is writing about? When and why, at some point between the Lascaux cave paintings and the Roman coliseums, did “we” turn away from animals? There are various hints towards this. Those of us who inherited the Roman world? Or the world of all those messed up taxidermy collectors who killed the mum and bottle fed the baby? But the culprits remain vague and unprosecutable. Perhaps the amalgamated “we” Carew pursues is as the animals see us; Prairie Dogs have a different call for “man” and “man with gun”. Or is it, as is regularly hinted, human nature itself, the Lascaux cave paintings not reverence but actually ‘one handprint of the many heavy handprints of the 100 billion humans who have ever lived’?

‘Most origin stories allow humankind authority over animals, and most peoples have degraded the land they have settled, and killed the creatures who lived there’. This is a strong claim that doesn’t feel sufficiently unpacked. It is uniquely human, we are told, to ‘Wipe out 200 million beavers, and then design a special box to parachute them back’, into wilderness areas from which they had been eradicated. It was an indigenous warden, Elmo Heter, who conceived of the parachutes to return the beavers. I’d hazard a guess he wasn’t the one, or the descendant and beneficiary of the ones, who wiped the beaver out.

These are big questions, and many, and one book can’t answer them all. But I was left feeling that the title is then a little misleading, in promising a ‘history’ and an ‘us’. I can get onboard with a little sprinkle of misanthropy as an antidote to widespread and destructive human superiority. And Beastly, it should be said, doesn’t wallow in misanthropy, balanced as it is by the portrayals of those humans who enact their love for animals. But, if it does claim it’s human nature that underwrites our inability to coexist with the other animals, then this book risks becoming self-defating.

‘The question of whether we are compassionate and cooperative or fundamentally violent and selfish has only one answer: we are both’. We are eventually reassured that we have the potential to change. Like 60 year old Devon sheep farmer Sivalingam Vasanthakumar, who was driving to the slaughterhouse with his lambs when he abruptly turned around and drove 200 miles to an animal sanctuary in Worcestershire. Whoever this “we” is, we can be like Sivalingam Vasanthakumar.

I can’t put my finger on this book. Like our relationship with animals, it’s ‘contrary and paradoxical’. Rhythmically, it’s more a palimpsest than a ‘history’; short vignettes, historical anecdotes, descriptions of YouYube videos. In a way it reflects the messy tangles of ecology, where everything is connected to something else. Beastly does enchantment work, rather than the grunt work of the hows and whys of our mistreatment of our kin. It is a wonderful book and what it does well is to make you snort and honk in laughter, woop at animal tenacity, and make you cry for our aching world — summoning your snivelling, animal, mammal self.

*

‘Beastly: A New History of Animals and Us’ is out now. Order your copy here (£19.00).

Read an extract from the book here.