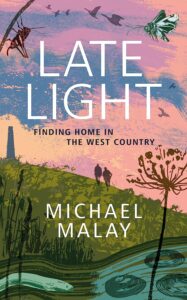

A book of little revelations, Michael Malay’s ‘Late Light’ will leave you aching with world-love, writes Abi Andrews.

Michael Malay’s title Late Light is homage to the particular feeling of ‘suspended time’ of late British summers. It can also be read as a symbol for the so-called anthropocene; a time in which we currently feel suspended in a moment that could still become dawn, or could be a kind of twilight. But back to those summers – the light has a quality that was first appreciated by Malay as a newcomer, arriving in Bristol after having spent the first two decades of his life first in Indonesia and then in Queensland, Australia. This suspension of light held a particular pull for a person who had grown up in the tropics, then just learning to feel what it means to wait for a season. And it is with the astonishment of a newcomer that we see the West Country landscape in the early parts of the book – with a careful attention that can perhaps only come from a person seeing for the first time; through it we are enabled to see things common to us anew. The weirdness of drystone walls or crooked medieval streets. The ‘strange insignia’ of pubs, and the bewildering idea that ‘if you wanted you could walk across the Severn bridge into Wales, another country’.

For Malay this strangeness also sits in a place that touches alienation. ‘At first, being a stranger here, I did not know the names for things, and so could not place myself in the landscape’. Fresh eyes helped Malay to see more clearly the places where our familiarity masks structural imbalances, and his true arrival unfolds as a deepening understanding of places where the England doesn’t fit together as it should. As a literature student having already built an idea of Britain before arriving, the ‘beauty of the landscape or the continuity of the past’, the British penchant for animal writing from a landscape that is so hauntingly defaunated becomes disconcerting. Getting settled becomes noticing more acutely what is really missing, ‘I was discovering a world of disappearing things’, instead arriving in a country that was ‘a much more complicated than the version of England I had carried in my mind’. But this deeper understanding becomes a kind of homecoming. Malay settles, and family life changes back in Australia, so that home no longer feels like a place to return to.

This complication of growing awareness that things are not quite right is recognisable to a person who may not have migrated but feels a kind of alienation from their home in a greater world under anthropogenic change. It is something many of us feel – the loss but also the wonder of being alive at this time of greater attention to what is disappearing. Following animals into their worlds, we come out changed. At the same time we add to our ‘growing apprehension of loss’, in learning more of the ways that their worlds are contracting. Malay speaks to our shared vulnerabilities via close attention to some unloved British species, ‘Animals who exist on the margins of our attention’: eels, crickets, moths and mussels. He presents wonderfully the motion and pull of the natural world left to its ebbs and flows; eels that return to the sargasso sea and moths that migrate in the wind above them. Here we find both grief and awe – like the pearl mussels who create their pearls as a response to the stress of particles entering their shell, as ‘lustrous answers to the shock of being alive’.

Deftly speaking of these animals alongside the socio-political forces at play in their lives, with a care that never removes their specificity and difference, Late Light is a beautiful meditation on the way that all earth lives are currently entangled. From migrating eels blocked by sluice gates to those humans whose safe passage is blocked by national borders, to water-people originally displaced from the fens, to the loss of habitat for wildlife, and the contemporary dismantling of common public spaces such as libraries. The underlying question of what it means for a home to become “dismantled” is expansive and generous; it might mean a dismantling that happens politically, physically, or even a more personal change that makes what home was now unrecognisable.

‘To respect our neighbours, we do not need to understand them’. The kind of ecological thinking that Malay writes from can make us more empathetic. ‘What if, by adjusting our scales of vision, we could touch the far edge of another’s experience?’ This call for empathy transverses both the human and nonhuman. But this is not a diatribe, Late Light is slow and considered, with little revolutionary ruptures. It sings to its own spirit that careful attention can make small things monumental. The writing is incendiary by stealth – not a lament, but a case for ‘attention and care’, for building a world that allows space for biological (taken to include social) diversity – in which we direct ourselves towards the opposite of extraction. Malay calls for ‘more generous ways of imagining the world’, which is, gorgeously, ‘the most outlandish pearl of all’. Late Light is a book of little revelations. It approaches small things with a quiet and tender profundity, and its attentiveness to the quivering of life will leave you aching with world-love.

*

‘Late Light’ is out now and available here, published by Manilla Press.