Ken Worpole writes:

The short autobiographical piece below was commissioned for a book that never happened. Writing in the first person is not something I feel comfortable with, to be honest, but on this occasion there was no other choice. I have spent a lot of time on trains travelling around the country, often noting that when a small group of friends or work colleagues travel together, it is invariably one person who does the talking: if it is a mixed group it is usually a man. Most of the books I have written have been based on listening to others talk about their lives and beliefs, and a mixture of voices and opinions is much richer to me than the single, linear monologue or life confessional. Unless you are Samuel Beckett.

The underlying drift of Gelato al limone is that the creative artistic and political ferment of the 1960s in Britain occurred as much in the provinces as it did in London. Suddenly everything seemed to be happening everywhere at once: the folk revival, the ‘ban the bomb’ movement, pop art, trad jazz versus modern jazz, civil rights protests, fighting racism, Beat poetry and the blues and rhythm and blues explosion in pubs all over the country. It helped if the town had an art college or further education centre where the nonconformists could gather; coffee bars with jukeboxes came in useful too. Southend had all of these, but so did Brighton, Birmingham, Bolton, Bristol, Cheltenham, Ipswich, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Cardiff, Swansea, and dozens of other towns and cities.

At a fund-raising party, Southend Labour Hall, 1962. Suit from Burtons.

I was born in a castle in 1944: Willersley Castle in Derbyshire to be exact. This was the place to which pregnant women in the care of the Salvation Army Mothers’ Hospital in Hackney were evacuated during the war. Afterwards my parents joined the familiar post-war exodus from east London, heading first to Canvey Island, and then on to Hadleigh, Thundersley and, finally, Southend. On Canvey we lived in Grafton Road — which, like many roads on the island was a muddy lane — no more than two hundred yards from the sea wall. Typical of the flimsy plotlands dwellings that sprouted up between the wars along the Essex coast, and where land was cheap, ours was a single-storey partitioned bungalow resting on brick piers, with a verandah at the front reached by open wooden stairs. Years later Wilko Johnson claimed these dwellings provided the authentic delta experience necessary for the Canvey Island delta blues.

As to schools, I attended Davies Lane Primary School in Leytonstone, Long Road Primary on Canvey Island, Hadleigh County Primary, and then, having passed the ‘eleven plus’ in 1955, went to Southend High School for Boys for five years. My class-mates included erstwhile rock music icons Robin Trower and Mickey Jupp. They may not remember me, but I remember them.

I was living in Thundersley when ‘selected’ to go to grammar school: a five-mile bus journey and long walk each way every day. As a result, my friendships and interests remained where I lived. I was never comfortable at the High School, which modelled itself on a public school and operated a rigid, self-fulfilling policy based on an inflexible streaming system. Within months of arriving, pupils sat an exam and were then placed in one of four streams, A, B, C & D, after which few if any changed classes ever again. Our C stream class might best be described as ‘bright but chippy’, and from time to time some of the teachers told us we would never amount to much. From such ressentiments are counter-cultures made. In the year above us, Viv Stanshall kept the exasperated teachers on their toes, while we could only look on in awe as he arrived most days testing the school uniform dress code to the point of destruction.

The friendships I made at the primary school in Hadleigh were long-standing: a small cohort of us moved from boy scouts to church youth club to skiffle group to Young Socialists without passing Go. An early and sentimental attachment to the causes of world revolution and international nuclear disarmament — I went on the Aldermaston March, protested in Trafalgar Square against the murder of Patrice Lumumba, and spoke from a soapbox in Rayleigh High Street on behalf of YCND — took up more of my time than homework or school activities, and I once booked Robin Trower’s band, The Paramounts (later to become Procul Harem), to play a fund-raising gig for the Young Socialists at the British Legion Hall in Hadleigh, for which I paid his older brother £10.

There seemed to be so much going on in and around Southend at this time — coffee bars, live music in pubs, political meetings, concerts, demonstrations — I’ve often wondered how much this was also to be found in every provincial town or city at the time? Was Southend special? I once told Roger Deakin that I envied him for his seamless transition from school to university and then on to a writing and broadcasting career, whereupon he told me that he envied me even more for my Southend music scene years. In fact, Deakin made two television documentaries about the Southend scene, and was definitely smitten with it. Others were too. In the 1998 Guardian obituary of Anthea Joseph — the folk music entrepreneur who ran the Troubadour Club in the 1960s — the obituarist cited Joseph’s account of the night she first staged Bob Dylan: ‘I was on the door at the Troubadour and I saw this pair of high-heeled boots coming down the stairs and thought, ‘Oh God, another Southend cowboy.’’

Not everybody dressed like extras in a Sam Peckinpah western. I remember Southend as being extremely fashion-conscious, partly because a large Jewish population now lived there, many of who had worked in the East End rag trade, and were running à la mode clothes shops and tailoring businesses in the town. My future father-in-law was the manager of one, as well as being a professional tailor in his own right. The Jewish community also imported some of London’s cosmopolitanism to the town, including the weekend family promenade or passiageta along the seafront, along with a European predilection for pavement cafes, ice-cream parlours and watching the world go by.

It wasn’t all peace and love. A lot of rural districts in this corner of Essex with Anglo-Saxon names — Rochford, Rayleigh, Wickford, Basildon, Tilbury — had their own gangs, which made out-of-town pub gigs somewhat nerve-wracking if rumours started that rival gangs were meeting there to sort things out. Fights at the bar or out in the car park were not uncommon. I remember an evening at The Crown in Rayleigh where Dave Berry — a lachrymose, introverted cult singer dressed in black — was performing, but few could concentrate on the music, conscious of the rival gangs assembling outside, accompanied by the sound of revving motor-bikes.

Too self-consciously cerebral to allow myself to fall under the influence of ‘pop music’, and something of a snob therefore, I went straight from Lonnie Donegan to Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. Political interests and activities took up increasing amounts of time. Our youthful crowd of often met in each other’s homes, where some left-wing parents’ record collections might include LPs by black artists such as Paul Robeson, Josh White, Mahalia Jackson, Odetta and Billie Holiday, as well as The Red Army Choir and symphonies by Shostakovich, alongside books by Albert Camus, Upton Sinclair, Ignazio Silone, Doris Lessing and Colin Wilson. The connection between music and politics stayed with me for a very long time.

An acute self-consciousness about who I was and what was going to become of me was resolved by leaving school at 16 and getting a job as a trainee civil engineer with a road-construction company, and enrolling at Southend Municipal College for a day-release course in Building Studies. I stuck it on and off for four years, graduating to working on large construction sites in Birmingham, Liverpool & Glasgow, living away from home in digs, and becoming increasingly unhappy. One weekend in the spring of 1965, on a trip back to Southend, I went to the folk club at the Blue Boar in Prittlewell, and met a girl called Larraine. It was a coup de foudre (I had learnt some French at school), and shortly after we married, and remain married still. I applied for a place at teacher-training college to study and teach English, and my life changed forever, for the best.

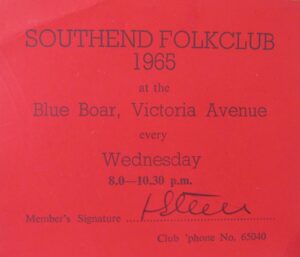

Southend Folk Club 1965 membership card for Larraine Steele, issued on her first visit, the occasion on which we met.

Aside from jazz, folk music reinforced this political worldview. The Blue Boar was special in that regard. On the night I met Larraine, Margaret Barry was the main act, an Irish street singer known as ‘the Queen of the Gypsies’, a formidable figure who mixed traditional Irish folk ballads with republican songs. Other performers at the Blue Boar who made a great impression included Rambling Jack Elliott (an early influence on the young Bob Dylan), Champion Jack Dupree, and a very serious A.L.Lloyd. During the interval people moved between the tables in the thick, beery atmosphere selling Challenge, the paper of the Young Communist League, or Peace News.

Many have attributed the lively music scene of the Southend area to the proto-American culture of the A13, with its mixture of heavy industry, low-grade arable farming and plotland (almost trailer-park) communities somehow intertwined. There is some truth in this. At its height, Fords at Dagenham (and later at Laindon, Dunton and Basildon) employed over 40,000 people and dominated the life of the northern Thames corridor. From the end of the Second World War onwards, waves of American music washed up on the shores of the Thames in south-east Essex, from Country and Western to show tunes, from New Orleans Revival to West Coast cool jazz, from blues to Motown. We had the roads, we had the cars, juke boxes, Burton suits, gelato al limone and Russian Tea, along with a street-wise, blue-collar culture born in London’s east end which had migrated out along the peninsula. Could it have been otherwise?

*

Ken Worpole is a writer and social historian. His most recent book, ‘No Matter How Many Skies Have Fallen: back to the land in wartime Britain’, is published by Little Toller. He blogs at https://