Our Book of the Month for September has been Tessa Bunney’s ‘Going to the Sand’ – a document of the last remaining fishing communities of Flookburgh. Occupying a space where landscape, portrait and still life rub shoulders, Bunney’s photographs find beauty in the unexpected, writes Helena Turgel.

I’m thinking about the link between beauty and space; space between, space gifted by frames, the unsaid.

In this book of photographs and occasional, densely packed clusters of words, form mirrors subject.

A landscape that is essentially all space, measured out in different elements — the broad expanses of land, sea and sky. And within those -scapes, occasional pockets of densely packed treasure for those who know how to find them.

Estuarine views that are never twice the same; all aspects of them shifting not only across days but within them; sky, weather, cloud, light, tide, water, reflection, ripple, sand, channel. Even down to the variegated offerings from the sea, laid out on the shore, and taken back again. Offerings that are hidden, but there for the taking if you know not just where, but how to look.

The images of these landscapes are sensual, they somehow reach beyond pure vision. They make you breathe differently; their expanse permits your own.

They remind me of the rare occasions I’ve met dawn when intoxicated only by sleepiness and wonder. This extraordinary majesty that happens each and every day. And in these pages are the folk who commune with it nearly as often as it happens, completely at the whim of tides who pay no mind to any reasonable sense of time.

In a single spread of prose we are given the context; Tessa Bunney in conversation with Colin Pantall. Snippets of fact interspersed with observations and musings. Snippets of conversation over a few years of visiting this place. Drafted with restrained economy. Space.

I’ve been thinking a bit recently about how we humans tell ourselves a story of how we are apart from nature. But that betrays the reality. We are nature, nature out of step with nature. Less so perhaps these folks. Tessa aligns them with our hunter-gatherer ancestors, these people whose survival depends on being fine-tuned to the elements that surround them. Survival in the sense of livelihood, but also actual survival. Quests for perfect mussels can take them out as far as 6 miles from shore, at which point they must time their foraging to the minute.

We of course know the tale of what happens when you do not. When that knowledge is not etched into your brain from childhood and within your body through lineage. The tragedy of the trafficked Chinese cocklers who lost their lives in these waters attest to what may happen if you do not.

Alongside the tragedies are the many other challenges faced by the fishermen of this region, from weather and fish stocks to permits and Brexit.

As with rest of the natural world, the inference is resilience. Tessa documents here an industry potentially on the brink of extinction, but surmises it will continue, perhaps in some part-time, side-hustle form, at least partly pickled for posterity.

And I hope that is true, because what is lost when these ways of existing in the world are gone is not just the livelihoods and knowledge, but also the hidden losses: the community that exists on the sand, the words to describe things that will no longer need to be described, the culture passed down through generations as carefully as heirlooms.

Going to the Sand is a book that, within its apparent simplicity, in fact plays many roles. Landscape, portrait and still life rub shoulders. Portraits of the subjects caught in moments of stillness and rest, others in the midst of their work. The images are given the space to speak on their own behalf.

Further reading is provided in pockets of text throughout the book and particularly right at the end, where the texture and hue of the paper changes. Mike Smylie’s interviews with fishermen give fascinating insights into every aspect of the life: the pleasing names given to the tools photographed (jumbos, riddles, craams); the markets that fluctuate as much as the fish stocks and the weather; the psychological studies of the creatures they fish.

There is also reference to the wider industry fed by the fishing — direct industry such as Baxter’s Potted Shrimp (from sea to pot, an arduous and fiddly multi-stage process that sounds completely delicious…secrets half told: a 90-year-old silver spoon and lots of butter!) — and also the industries that enable this capricious livelihood, such as the market gardens that emerged out of the move from horses to tractors (empty fields) but have now dwindled thanks to supermarkets.

It’s hard not to feel a kind of nostalgia for these ways of working, but in truth the romance of this way of life is exaggerated by the lack of proximity to it. Adaptability and tenacity are required.

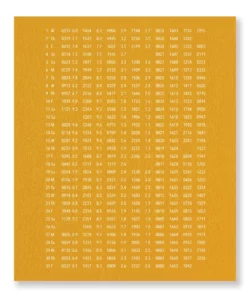

It’s a beautiful book; an artefact that nods its head at other artefacts. The fishing apparatus individually photographed in spreads you would hang on your wall. The tide table on the cover looking like it has been raked by the same tools dragged across the sand in the photographs inside. And cockles looking like they themselves have been scored by the craams used to excavate them. The overlaps between the so called man-made and nature-made unfold within the pages and muddy the line. Hi-vis workwear reflects the dayglow skies.

The beauty in the unexpected is unearthed by paying close and careful attention. Tessa Bunney appraises these landscapes, their people and their tools with the same attentiveness as her subjects pay their surroundings and their work.

*

‘Going to the Sand’ is out now, published by Another Place Press. Although the edition is mostly sold out, a few remaining copies are available directly from the artist — email info@tessabunney.co.uk or message her on social media to buy.

See an extract from the book here.

An exhibition of photographs from ‘Going to the Sand’ opens in Liverpool on 12th October. More information here.

Helena Turgel lives close to where the river Teifi meets the Irish sea on the westerly edge of Wales. She works for Mwldan arts centre, where she curates and produces talks for Other Voices Cardigan festival. You can find her occasional musings on Instagram.