Michael Morpurgo’s ‘All Around the Year’ — a record of the author learning to farm — is just-published in a new edition by Little Toller. From ringworm and foot rot to a cow with a cough, this is the sharp end of farming, writes Melissa Harrison — where sustenance and meaning are drawn from hard work and close attention to the living world.

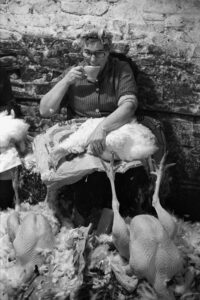

All accompanying photos: James Ravilious, © Beaford Archive.

In 1975 Michael and Clare Morpurgo, both teachers, moved to the little village of Iddesleigh in north Devon with their three children. With money left to Clare by her father Sir Allen Lane, founder of Penguin Books, they bought a large house, Nethercott, and the neighbouring Parsonage Farm, and with the help of their neighbours the Ward family – John and Hettie and their four kids, tenants of Parsonage – set up the charity Farms for City Children. The plan was for kids to come and spend a week helping out on a mixed farm (dairy and beef cows, sheep, pigs and arable, along with some poultry and horses) so that they might develop a connection to the countryside and share in the benefits both Michael and Clare felt they had gained from time spent outdoors growing up.

But before they could invite their first batch of children Morpurgo himself had to learn how to farm, and this year-long diary is a record of his apprenticeship under the expert guidance of the Wards. Their friend, the poet Ted Hughes, who had a farm called Moortown at nearby Winkleigh, and whose idea it was to publish the diary, offered to contribute a poem for each month, while another near neighbour, James Ravilious, son of the artists Eric Ravilious and Tirzah Garwood, took the photographs that illustrate it. He was at that time a couple of years into what would become a 17-year commission from the Beaford Archive to ‘show…North Devon people to themselves’.

All Around the Year glints, here and there, with lovely images, but the diary is primarily a record of of the daily rhythms of animal husbandry and sheer hard work: mucking out, clearing ditches in the rain, twice-daily milking, moving sheep about. It is full of the practical matters that make the difference between success and failure: milk yields per beast, prices at market, government subsidy calculations, lists of cows that have been inseminated, inventories of hay bales, the cost of sheep nuts. These details are included because Morpurgo really is teaching himself what to pay attention to – there is an immediacy and transparency about the diary entries quite unlike something written for a literary market well after the event – but also because they tell the actual story of farming much better than passages of high-flown description ever could. Selling stock, laying in food for winter, keeping on top of mastitis and foot rot and ringworm, working around unpredictable weather: this is no vanity project but the sharp end of farming, day in, day out. Hughes’ muscular poems open out the close focus of the entries and lend descriptive context and no little glamour to what, let’s not forget, was at the time the diary of a rookie farmer written by an unknown teacher.

Every task, no matter how menial, is given its meaning and context so that what swims into focus as the diary progresses is a pattern of work that constellates around the seasons and the needs of the animals, and through it it becomes possible to see that what may be relentless is also rewarding, in a deeply atavistic way. We begin to know the livestock, and the people, too: we worry about Emily, a cow with a cough; hope that Bounce, the young sheepdog, will learn his trade, and that the new cockerel will settle in; we hold our breath as lambing unfolds and cheer on the building of a new milking parlour so that one of the Ward’s grown-up sons won’t have to bend so much and his hip stops playing up.

The 1970s can seem both yesterday and a hundred years ago. A man in the village ‘blesses away’ the yearlings’ ringworm; people struggle with the change from Imperial to Metric measures, and the farm transitions from 10-gallon milk churns to a huge, refrigerated bulk tank. The lane is still lined with elms, which must be watched for signs of disease; hay is baled and stood up to dry in stooks, by hand, while the local hunt kills two dog foxes, but misses a vixen, who cries out in the dark.

All Around the Year came out in 1979; War Horse, partly set on Parsonage Farm and inspired both by local men who had survived the trenches and the relationship between one of the city children and their horse, Hebe, would be published in 1982, and its sequel Farm Boy, also set on the farm, in 1997. So beloved is War Horse (and the play and film that sprang from it) that the area around the village has become known as ‘War Horse Valley’; its author was made Children’s Laureate in 2003.

Farms for City Children welcomed its first visitors not long after this diary ends, and the charity went from strength to strength: now with three properties, one in Pembrokeshire and one in Gloucestershire, it continues to host young people from disadvantaged areas, opening their eyes to a different way of life. Over 100,000 children have now spent a week at one of the charity’s farms, and while agriculture has changed a great deal since the mid-70s the world the kids encounter is still the one which Morpurgo discovers in these pages: one in which people can draw both sustenance and meaning from hard work and close attention to the living world.

*

Sales of this new edition of ‘All Around the Year’, republished by Little Toller and with a new introduction by Katherine Rundell, will support Farms for City Children. Buy your copy here (£15.20).