A new anthology collecting the words and images of the wood engraver and writer Clare Leighton, issued by Bodleian Library Publishing, is our October Book of the Month. Nicola Chester reviews, finding work infused with the lyricism, beauty and connection of rural labour. All images © The Estate of Clare Leighton, 2023.

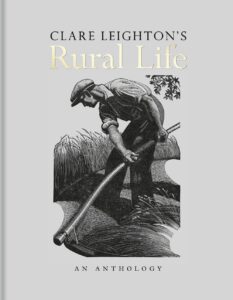

Rural Life, the new anthology of Clare Leighton’s (1898-1989) writing and illustrations, is a thing of workaday beauty. Cloth bound in hessian dove-grey, her ‘scyther’ on the front (Leighton’s partner at the time) is wrought with such poetry of movement and the intricacy of the falling grasses (cocksfoot, timothy, fescue) with its title picked out in gold, as if from the light on a brass implement. Such is Leighton’s work, infused with the lyricism and connection of rural labour.

A prolific wood engraver of the early twentieth century, Leighton completed around 850 prints, illustrated more than 65 books, wrote 14 herself and produced designs for cathedral windows and Wedgewood plates. She was also a celebrated speaker. This book covers a lot of ground, and conveys a deep insight into Leighton’s ever-relevant vision and work.

The book is dedicated to her nephew, David Leighton (1931-2022), lifelong devotee to her work and editor of this anthology, who sadly died before publication. He writes that his aunt ‘had a way of detecting the essence and the value of all human beings.’

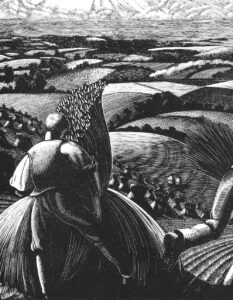

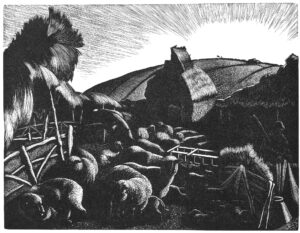

Her art of peopled, working, rural landscapes is at once muscular and tender, humble, yet epic; her subjects bent in a kind of reverence to the earth, their tools and toil, or fronting the sky and weather.

The book’s chapters are not chronological — we begin with excerpts from The Farmer’s Year (1933) in which Leighton records a fading way of life and skill, at the point of mechanisation. Her engravings bear witness, and are as tribute, rather than an act ‘fixed for the sightseer’ of sentimentality. Here is a farmer, sleeves rolled up, walking a mighty stride across the plough, his trousers tied at the knee, ‘who still feels some warmth come up to him from the earth as he strides the fields…a god, flinging his bounties upon the world.’

Leighton’s writing here is elegiac; written with an artist’s eye. A farmer’s wife ‘white-limbed as an open hazelnut’ works where ‘hens stray into the cider barn, each one bringing in front of her a little purple shadow.’ In August, ‘all green things flag…full of life’s fatigue’ yet all hands and any are welcomed at harvest, where ‘the glamour of the sheaves blends all.’ Here too is the gleam on hobnailed boots, a Romany Rai on the steps of his vardo, a threshing team, and a ploughman turning his horses and share on a serpentine into the sun — all is elegy and immediate, and full of power: light, dark and shape.

Leighton was a pacifist, ‘since burying the stained and tattered uniform of her [nineteen-year-old] brother Roland’ in 1915. He and their friends were immortalised in the memoir Testament of Youth, by Roland’s fiancé Vera Brittain, in 1933.

Four Hedges (1935) details some of the work Leighton and her partner, the political journalist Noel Brailsford, undertook on an unforgiving plot of wild, chalk ground. She feels a separation from it, until she throws off her gloves, ‘her restraints and respectabilities’ and digs in, no longer a spectator. Leighton was instinctively sensitive to the soil and nature. She was also funny, recording how autumn colours intensify if one looks at them upside down, between one’s legs.

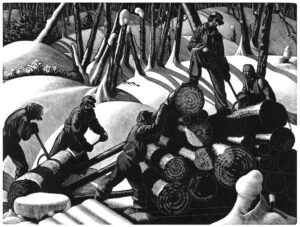

Her stay with Canadian lumberjacks in 1931, deep in the snowy forests of the Laurentian Mountains of Quebec is recorded in intimate, joyful and intrepid diary form. She walks alone in a wolf-haunted wonderland, falling over her snowshoes and eating with the men. She describes the ecstasy of travelling 26 miles with them on horse-drawn, belled sleighs, wrapped in bearskins. Her black and white media lends itself beautifully to the depictions of deep snow (‘like great night-caps’) and the work in dark, hushed forests. You can feel the weighted blanket of silence and awe.

The jump to her earliest works make for a pause — but only to recognise the foundations to which she always then held true. In 1920s Toulon, she depicts washerwomen, spinners, mussel harvesters, creel-menders and marketsellers.

In 1939, aged 41, with WWII painfully looming, Leighton left her now ‘demanding and jealous’ partner to lecture in America, and did not return. She made friends among the workers she illustrated, as well as academics and artists, and found work to support herself.

Southern Harvest (1942), a book she was shy of proposing (mid-war and not a little homesick), helped her root herself to her adopted country. ‘I felt that it would be only among the workers that I should find comfort, [and the] universality about the people of the soil that transcends frontiers or racial ideologies.’ Southern Harvest included folklore, farming methods and addressed a legacy of slavery. Engravings from this time feature sugar-tappers and apple-butter makers, as well as whiskey ‘moonshiners’ and Black cotton pickers in the Mississippi Delta (though the latter two are not featured in Rural Life.) Recalling plunging her ungloved hands in the earth at Four Hedges, she speaks fondly in a lecture of working with her ‘very great friend,’ George, an elderly Black gardener, in North Carolina. He suffered with rheumatism in winter, and Leighton would massage his legs to relieve the pain. But he rejoiced in the warmer months, insisting on the healing quality of contact with the earth and worked barefoot — Leighton readily joined him, delighted to share the same belief, in practice.

In a shaky post-war Minnesota, Leighton addressed the need for ‘our gardens now more than ever’ for social cohesion, as well as racial; and for mental health and the bedrock of ‘belonging,’ wherever you are from. It’s a mantra that defines much modern writing on nature.

She never forgot her time teaching art (as an art student herself) to schoolchildren in the poorest slums of London (who she taught to see beauty in the light and shape of chimney pots) or the ‘heartbreaking letters’ she received from children listening to her gardening programmes on BBC Children’s Hour, wondering where they might find soil, or a garden. She wrote back with instructions for tin cans and spoonfuls of soil and seed from the nearest park. Something she did herself, when living morose and detached in a gardenless flat in Baltimore, when her own tin-can garden revived her.

And here are her messages for our times, fresh as a boxwood shaving: ‘if I am defiant in my defence of the countryside, it is because I know it is the last hope for sanity…the strong, sane humour of the earth, without which there is no health. At no time has this been more needed, and at no time have we been at greater risk of losing it.’

Clare Leighton, ‘artist as quickener of the world’ died aged 91, after a life of nature, creativity and work, peace, friendship and the expansive arms of inclusion. This is a book very much for our time.

*

‘Clare Leighton’s Rural Life’, edited with an introduction by David Leighton, is out now (£30, Bodleian Library Publishing). Order your copy here. Read an extract from the book here.

Nicola Chester is the author of ‘On Gallows Down: Place, Protest and Belonging’. You can follow her on Twitter here.