Laura Parker tells the story of a 1928 lifeboat tragedy, as memorialised in the windows of an East Sussex church.

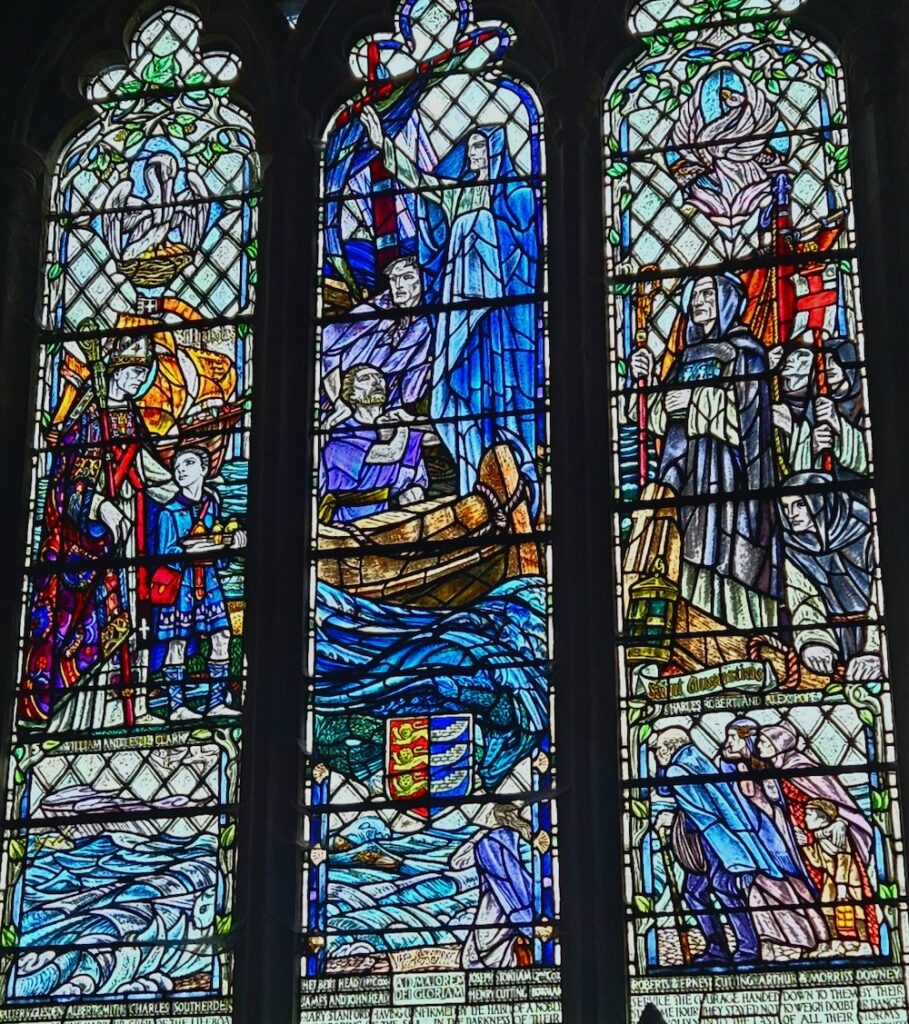

In brilliant cobalt, amethyst and jade, a dragon writhes beneath a solemn angel. God’s armour-clad messenger stands upright on the beast’s coils, a pointed staff in his right hand, a chain in his left. As he subdues the red-eyed sea monster, shoals of green fish pour around his helmeted head. Above this scene, three trefoil windows bear the words of Psalm 107: ‘Those that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters, they see the works of the Lord and His wonders in the deep. He maketh a storm calm…so He bringeth them unto their desired haven.’

At the bottom of the large window, three small ships sail into harbour. There are houses, a high wall, and trees.

It’s been five hundred years since any vessels have been able to sail up the sea inlet to Winchelsea. Today, the nearest piece of shore to this stranded Cinque Port is the shingle beach where the Old Lifeboat House stands isolated and decaying. At just over a mile from the village, it is the same distance that seventeen men ran in the dark through driving rain from Rye Harbour village on the morning of 15 November, 1928. Roused at 5am, the crew of the Mary Stanford, a fourteen-oar ‘pulling and sailing’ Liverpool class lifeboat, set off through blinding spray into a south-westerly force 10-11 gale in an attempt to reach the stricken Latvian steamer Alice of Riga. Woken by the maroon – a loud rocket used to alert lifeboat crews – eight-year-old William Stonham had sat at the top of the stairs watching his father Joseph struggle into his oilskins.

“Here, Dad, take my torch”, he offered.

“It’s alright, son, I won’t need it, I won’t be long”, his father replied.

At 6.50am, Rye Coastguard received a message that the Alice’s crew had been rescued. It tried three times to recall the lifeboat. At 10.30am, young Cecil Marchant, out collecting driftwood on Camber Sands, saw the Mary Stanford apparently heading for port. Suddenly, in a bright shaft of sunlight, the boat capsized. Neither Joseph Stonham nor any of his crewmates survived. The bodies of fifteen men were washed up that morning. Five days later they were buried in a communal grave following a funeral procession observed by hundreds of mourners and reported all around the world. Of the others, one was washed up at Eastbourne three months later and another was never recovered. The disaster had wiped out nearly all of Rye’s fishing fleet.

By 1929, Scottish artist Douglas Strachan was an established creator of stained glass windows, with works in Aberdeen, Glasgow and The Hague. A few years earlier, his daughter Una Wallace had driven with him past the church of St Thomas the Martyr at Winchelsea and noted its plain glass windows: “Look Daddy, at all those lovely empty windows for you to fill!”

Within months of the Mary Stanford disaster, Strachan was able to do just that. Scottish peer Lord Blanesburgh, seeking to commemorate family members lost in the Great War, commissioned Strachan to design the stained glass he had donated to the church. The three windows on the north wall were to represent the elements of earth, air and water. Strachan placed the underwater dragon and its commanding angel in what is now known as the Sea Window.

But the first piece he created was in the south wall. The Lifeboat Window’s most striking central image is the prow of a wooden boat. A fisherman in purple with a yellow sash sits within, praying, while Christ stands above him, calming the waters. On the right, St Augustine, the first Archbishop of Canterbury, is landing on the Kent shore. On the left, St Nicholas, patron of sailors and children, is shepherding a young boy holding a toy boat with figures in it. Above the heads of the saints are representations of a pelican and a phoenix, symbols of self sacrifice and resurrection.

At the base of the window are three smaller sections. The left-hand light shows a stormy sea, and in the central section, a tiny boat is tossed on the waves. On the right, a small group wearing biblical cloaks watches intently from the shore, an older man at the front leaning on a stick. A couple bend anxiously into the wind, the woman’s arm wrapped protectively around a small boy holding a lamp. Amid the names of all seventeen lifeboatmen inlaid into the base of the window is a Latin inscription: AD MAIOREM DEI GLORIAM. For the greater glory of God.

*

Laura Parker lives in Oxfordshire where she keeps a small flock of sheep. She writes about nature and culture for ‘Country Life’ and her work has appeared in ‘The Clearing’ and ‘Spelt’ magazine. Follow her on Instagram / Bluesky.