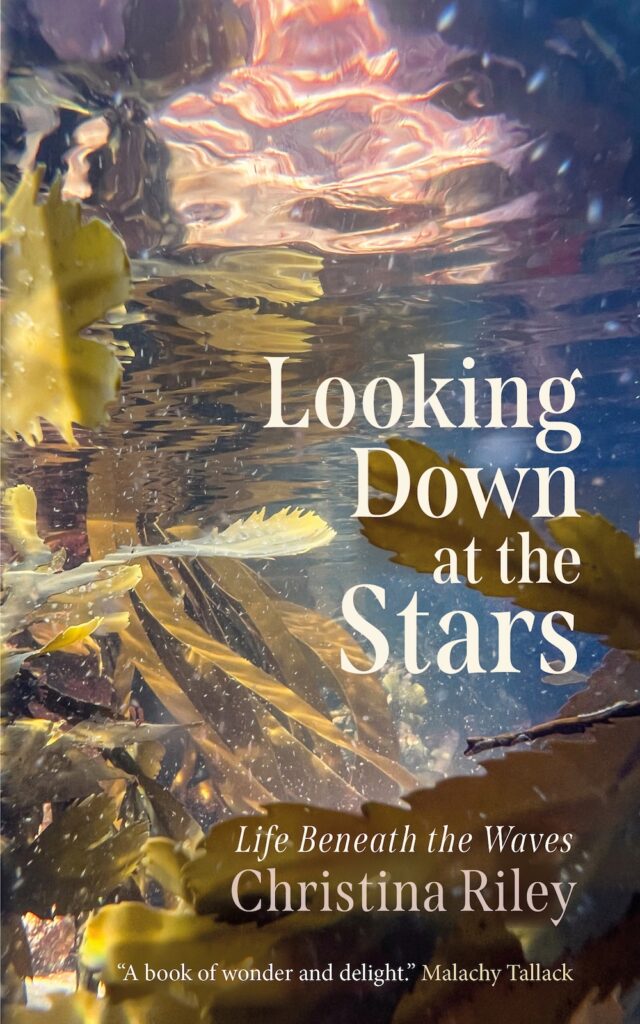

Christina Riley’s ‘Looking Down at the Stars: Life beneath the waves’ gently leads us to a love that is born from looking — and to hope, writes Kirsteen Bell.

Anyone who has ever knelt at the cold rim of a rockpool or stood ankle-deep at the edge of the sea knows that feeling of wanting more: of yearning to glimpse even a fraction of ocean life. For artist and writer Christina Riley, it was an artist residency at the Mission Blue Hope Spot in Argyll that allowed her to tip forward into these west coast waters, ‘ready to meet those living below the surface’. The observations, experiences, and reflections that emerged became Looking Down at the Stars: Life Beneath the Waves.

The intricate coastline around the Sounds of Jura and Mull is the first designated Hope Spot in the UK, joining a global network of community-identified areas whose biodiversity is critical to the health of the ocean. I am fairly familiar with these waters – I live nearby the inshore sealochs Riley describes, and I am married to a mussel farmer – but I don’t know them the way Riley has seen them. I have never floated for days, immersed in that kaleidoscopic aqueous world. And so, knowing too Riley’s eye for the seascape, I went into this book with real anticipation.

It is a slight book; its form echoes light glancing through seawater to reveal the extraordinary. It reads to the mind in the same way eyes sweep across the surface from shore to horizon, shifting your perspective as you dip in and out of the water.

Riley’s words tug you lightly into the current. Brittle stars move with an uncanny dance, ‘a supple indifference that borders on horror’, ‘creatures the colour of candy collect in clusters writhing with million-year-old grace’, scallops have two hundred eyes, ‘each one made of tiny mirrors, each mirror a mosaic of living crystals’, and sea lemon eggs unfurl ‘like the flesh of an apple ribboned into a rose’.

Fragments of knowledge and imagination flicker in and out of view, like sunlight in seagrass, occasionally defining the edges of Riley’s wonder. You will find a box full of sunlight, a limpet shell she can perch on; mussel shells that grow like a human heart, and seaweed that crystalises into sugar kelp. Riley’s meditations bubble up throughout, as she captures the thoughts that come from her observations. The value of art in a burning world is considered alongside factors that influence the way we think about the sea, or the ways in which we interact with lives and ecosystems both seen and unseen.

While not memoir, or even ostensibly about Riley, there is a sense of her growing relationship with the sea and its life. She recognises the residency becoming a threshold between the water’s edge and its true depths. In doing so, she gently brings us along with her as she submerges. From gathering morsels of stone and shell to steady her on land, she applies her photographer’s mind and eye to the transience of submerged life. The constant movement of tide and drift stirs Riley’s sense of the environment, simultaneously ancient and new to her, and she is honest in the questions those dynamics raise. We bob along with her, invited to consider those unanswered issues in the context of a dimension that is familiar while also out of reach of our full understanding.

I confess I itched occasionally for a little more explanation about the creatures’ inner workings (Lightbulb squirt! What?!), but that would be missing the point. The writing ebbs around the underlying premise that we don’t have to comprehend the inner workings of a life to love it. This idea comes to the fore in her discussion with wildlife cameraman John Aitchison, who is one of the community members behind the Hope Spot residencies. The questioning and curiosity that are so strong in Riley’s work chime with the questions Aitchison hoped to see explored: ‘What lives here? Why does it matter? How is it doing? How can I help?’

The words of writers such as Rachel Carson round out that exploration, as Riley draws on the philosophies and experiences that contribute to her own ways of interpreting the intertidal realms. However, it is when she leans into her personal reflections that the waters are most clear, the glancing light of her attention illuminating the connections she creates between the magical and the real. Beauty and wonder sharpen into focus, glittering against the context of human disregard.

Her anger and bewilderment at the cruelty and ignorance of human leaders is bright, whether it is directed at the fishing-depleted ecosystems of her home waters of the Clyde, or on the Tel Aviv Hope Spot that’s been a home without borders to blackmouth catsharks for millions of years, its harmony a stark contrast to the devastating realities on land.

Sometimes I imagine world leaders – the ones killing and getting others to do the killing for them – I imagine them frolicking into the sea. I imagine them on their knees staring into rock pools or running out the house in their pyjamas to see the aurora borealis dance above their heads, gazing upwards, letting magnetic light fall from the heavens into their open mouths, standing next to their neighbour and feeling, fleetingly but collectively, that right now this is the most important thing.

As we look down at the stars with Riley, we are nudged to question too. To consider how small acts of wonder can ripple out to have greater implications and impact on the way we live on the Earth. The fragments of writing coalesce to suggest that we don’t always have to understand the mechanics of something to bring it into our individual or collective attention spot. Instead, we are gently led to a love that is born from looking. To hope. These are the active emotions below the surface of this book that might motivate our respect and care.

*

‘Looking Down at the Stars: Life beneath the waves’ is out now and available here, published by Saraband. Read an extract from the book here. Read this month’s paid-subscriber-exclusive interview with Christina, touching on the writings of Rachel Carson, seeing the world through a scallop’s eyes, and the inherent poetry of the sea, here.

Kirsteen Bell is a Scottish writer of narrative non-fiction and sometimes poetry. All her words are gathered from the croft in Lochaber where she lives, and the surrounding Scottish Highlands. Her writing and reviews can be found in such places as Paperboats, Caught by the River, The Guardian Country Diary, The Lochaber Times, and Northern Scotland Journal. Kirsteen can also be found at Moniack Mhor, Scotland’s Creative Writing Centre, where she is Projects Manager and Highland Book Prize Co-ordinator.