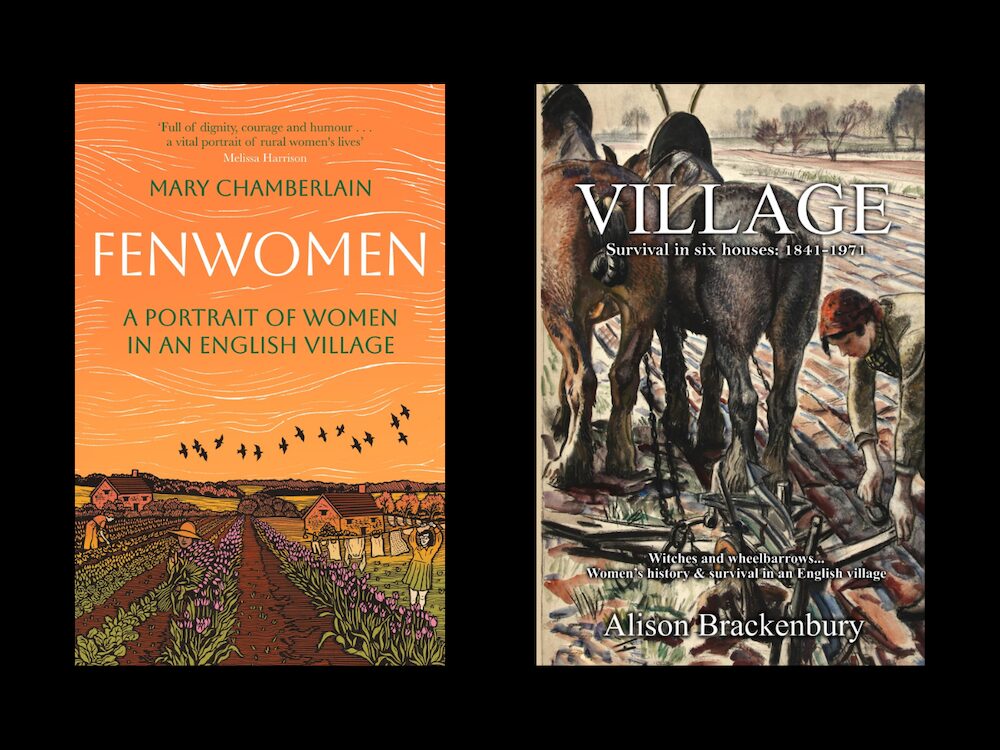

Alison Brackenbury’s ‘Village’ and a re-issue of Mary Chamberlain’s classic ‘Fenwomen’ give voice to an otherwise largely silent corner of England, writes Nicola Chester, telling the evocative, hard-lived stories of rural working class women.

A re-issue of a classic, and a wonderful new book by the poet Alison Brackenbury, give voice to an otherwise largely silent corner of England, only really known through books such as Flora Thompson’s Lark Rise to Candleford trilogy, or glimpsed in the lit doorways of Ronald Blythe’s Akenfield interiors. Fenwomen by Mary Chamberlain, and Village by Alison Brackenbury add vividly to the slimmest of cannons, telling the evocative, hard-lived stories of rural working class women.

Fenwomen: A Portrait of Women in an English Village, is the 50th anniversary edition of the first book published by feminist press Virago in 1975, founded at a hugely progressive time for women’s equality and liberation. Mary Chamberlain tells Kirsty Wark on Radio 4’s The Reunion, it was undertaken as a feminist Akenfield, to record the other 52% of those rural voices, either side a period of great change in the countryside.

Chamberlain’s women talk candidly (their names poetically reimagined) from the early 1970s, looking forward, but also back as far as the 1890s. Alexandra Harris, historian and author of The Rising Down, calls it, in a new introduction, ‘a collage of women’s voices…echoing, countering, and continuing each other’ under what Chamberlain calls ‘the great cupola of the fenland sky.’

Here are shadow lives, constrained by husbands, children, the provision of food on so little, and a watchful eye on outsiders, and each other. Days of the harshest field work, bookended by endless domesticity. Mothers give voice to their mother’s labours and, in a limited arena of possibility and choice, opinions and ambitions are tempered by necessity and close horizons: marriage for survival or conformity, and the accumulative hardship of many children.

It is deeply affecting in many places, but full of dignified, astonishing resilience, pride and love, too. Here is Mary Coe, 86, recalling the importance of gleaning individual ears or grains of wheat, after harvest, to supplement the year’s meagre bread, while babies, strapped to their backs, sleep on in sugar-and-laudanum induced oblivion.

Meg Ladell, 51, highlights the unquestioned sanctity and stoicism of marriage; an uncaring father that returned periodically, in smart clothes and new shoes, when his large family had so little. Meg recalls the practical kindness of a neighbour, bringing a large bone to make broth with, when there was nothing to eat. ‘There was no joy in my life’ she says, ‘only the love Mum and I had between us.’ Gladys Otterspoor laments a mantra of unfairness repeated: ‘little girls all help mummy’ and are not allowed to play like the boys. Families sometimes had to pack up and go to the workhouse for winter and as soon as girls were old enough, many, like my own Northamptonshire Nan and her sister, were sent to work as maids in a ‘big house in service.’ But it meant travel of sorts, new faces and a smart uniform (that came out of your wages) if little respite.

The lives of the women are lifted by concerts at village halls, clubs, fairs and humour: Aida Hayhoe stays up mending into the night, grateful for the excuse to miss sex with her husband, and more children.

So much has changed, though it’s extraordinary what lingers. Women were interested in politics, and influenced their husbands, but Lucretia Cromwell, married to a farm labourer, says ‘you had to vote Conservative…the same as your master did’ or lose your job. Some of these half-feared, or wrong-headed traditions linger; whether emulation, aspiration or oppression, who can truly say? And who can say whether reluctance to leave a village and broaden horizons is borne of the lack of opportunity to do so, or love and contentment, or an inherited, generational obedience and lack of confidence in your own worth and voice? As a former governor of a rural secondary school myself, I can vouch these conversations still happen in earnest. In 1970s Gislea, the real fen village of Isleham, girls aspire to be hairdressers briefly, or just get married and stay. Though there is Fiona, who wants ‘to be a horse trainer. Or a dentist – not a real dentist [the audacity!] but a dentist helper’ and Elizabeth Thurston, the first woman elected to the Parish Council.

Place anchors and holds these women, as an extension of themselves, but it takes ‘an outsider,’ Laura, to speak of the singular beauty and strangeness of a ‘fen blow’ that, she admits, means ‘crops lost and a line of dirty washing’ to others.

The Fenwomen are as ‘isolated, frustrated, rebellious’, as the black fen itself, ‘unspeaking, invisible’, as Alison Brackenbury describes them, yet heard, here. A debate over the provision of a nursery, is a conversation between the village and the modernising outside world, and is enlightening and wry.

In a new afterword, Mary Chamberlain, bestselling author and historian of Britain and the Caribbean, describes the early 1970s as a time when women’s history didn’t exist, and no woman could access loans or a mortgage. This was a male prerogative until 1975, the year Fenwomen was published. Chamberlain also points out, from a 2025 viewpoint, that the white women of the sisterhood barely yet understood the extra forces of oppression felt from a racial, ethnic, religious, differently abled, gender or sexuality-based experience.

Marjory wins a scholarship to high school, as Brackenbury did to Oxford University, aged 18; but Marjory’s ‘mother couldn’t afford it’ so she didn’t go. I make connections with rural NEET children now (those ‘not in education, employment or training’) and see my daughter among the figures, denied a bus to further education, but, because we can drive her (and she’d rather) works part-time and volunteers to gain experience. Marjory takes a job serving students at a college she could have gone to. Unable to bear it or the servile uniform, she returns to work the land she loves instead. She tells Chamberlain she liked to talk to educated people ‘even though I couldn’t converse with them…it stimulates my brain. I feel that something in me is at home – I’ve come home to roost, like a bird.’

After publication, The News of the World feigns a cynically predictable scandal, setting up Fenwomen as a tell-all betrayal by the author, exposing the village and its women where they are most vulnerable: trust, reputation. Mary Chamberlain is resented by those who don’t bother to read the book. Again, a note of rueful familiarity: wrongful accusations in an Amazon review on my first book, On Gallows Down, sparked a spell of village Facebook nastiness.

Poet Alison Brackenbury mostly speaks only of the dead, in Village: Survival in six houses, 1841 – 1971, an evocative prose book she has ‘been working towards all [her] life.’ Unlike Chamberlain to the Fenwomen, Brackenbury is of her village, and generations of horse keepers, shepherds, lacemakers and cooks. Her wonderfully rich blend of memory which ‘began with cheerfulness,’ and startling research is an extraordinary tribute to the women in her much smaller Lincolnshire village. With the exception of The Manor, the six houses are humble: two cottages, a tradesman’s house, a farmhouse and a bungalow. The book is moving, funny and revelatory about lives of which we know so little, and there is also a kindness and tolerance evident in Brackenbury’s village, that seems less present in Gislea/ Isleham – but I wonder if the difference is not between the hardness of the lives of two villages, but the methods in which their stories are narrated and collected: a chronicle reported, a book gathered. Brackenbury’s village is not static, and she finds, as I have about my fellow villagers in the last century, they tend to be more accepting of each other’s flaws, mistakes and differences, than is often credited. Their lives, after all, lived in close proximity and interreliance.

Village is a glorious, generous compendium. A selection box of delights and a romp through stories, censuses, census collectors and revelations, that overlap in layers, like a coloured tissue-paper lantern. Intertwined lineages rival the generational complexity of Wuthering Heights. Here are drunk carters driving into ponds and cottage lacemakers, with the equivalent of manifesting, inspirational quotes written on their bobbins (Buy the Ring!) and spirited Emma Jarman, who liked a drink of a Saturday night, and came home in a wheelbarrow for a taxi. These are lively, vivid communities, adapting, like the indomitable Weatherhoggs, harness makers, saddlers, census takers, wheelbarrow-taxis and bicycle makers, to changing times and circumstance. Even the Black Dogs of Lincolnshire folklore are kindly chaperones here. Mary Ann, teenage mother of an illegitimate child, is accused of witchcraft and murder three times, yet survives in her tiny cottage under a walnut tree, to live contentedly with her skilled Black horseman ‘lodger,’ Issac, in the last decades of the 1800s.

Brackenbury describes Village as ‘an attempt to hold back the dark’ and it does. It is Hardyesque, recalling the women’s lives of Lark Rise to Candleford, and is similarly anti-nostalgia. In the fields, damp cottages and cold Manors, people have accidents, die young and do bad things to each other too; ‘No vaccinations’ is a repeated lament: ‘The women of the Victorian village lived at war…they pitted bars of soap and their own formidable strength against enemies they could not foresee and scarcely understood’ such as diphtheria, typhoid, phthisis (TB). Full of the most beautiful, poetic language, there is Alison’s grandfather’s memory of his mother, Mary Brackenbury, waiting for her shepherd husband John to come home to their fire-lit cottage: ‘that apron, glimmering like a moth at the gate, was proof that love survived.’ John died young, contracting pneumonia after sleeping on damp straw, in the same year their tenth child died. Mary receives ‘Parish’ help until told she is strong enough to work. Her nine remaining children survive, though she does ‘not live beyond 50.’

Brackenbury’s father was an agricultural haulier in a village where ‘high masts of Brussels sprouts leaned drunkenly, furred by frost’ where ‘men in battered boots cycled off to fields [as] women stayed inside, in dark kitchens.’ Unlike Dot, a beloved grandmother and cook, young Alison wanted ‘air and animals and horses.’ Included are wonderful photos of her family’s magnificent spherical and square Romney sheep, worthy of The MERL’s Absolute Unit fame. The author knew and was influenced by the incredible Mrs Rudkin (1893-1985). Governess, groom, married and widowed by 25, she became a pioneering archaeologist, folklorist and historian, uncredited for her valued work on Ordnance Survey maps, with the profusely apologetic C W Philips (who himself led the 1939 excavation of the Sutton Hoo burial ship.)

There are modern voices and thoughts too, and plenty of lines resonate: ‘If you grew up in a ‘tied’ house, the fear and uncertainties of ‘flitting’ stay with you.’ Alison revisits Mr Weatherhogg’s shop online; a holiday let with white walls and bedsheets, and imagines a charwoman sinking into the sofa before a vast screen.

Both books put me in greater awe of the forgotten, unmarried women-in-their-40s-and-50s, that inspired my new book Ghosts of the Farm; how they farmed, led and changed their communities for the better, without deferring to a husband or father. Throwing themselves energetically into progress and social cohesion, while never forgetting the past. But of course, Fenwomen and Village also throw a lamplight beam onto how ‘my’ pioneering women managed it: with the agency and leverage of class and means.

Both books corroborate and validate my own experience as a rural working woman and will find resonance or illumination with many. They show where the hesitation and uncertainty comes from in a life, and the lives before, that have influenced and shaped those after: the ruminative doubts when you might dare to reject the status quo, the accepted politics and beliefs. The sharp reminders to, above all, know your place, that comes from the love, protection and precarity of those previous generations: the wives and daughters of those Ag Labs and ‘flitters,’ fruit pickers and ploughmen – the women always in service. But what they give back, with joy and affirmation, is tenacity, resilience and dignity; voice, and the song of a rightful place in history.

*

‘Fenwomen: A Portrait of Women in an English Village’, newly re-issued as a Virago Modern Classic, is out now and available here (£10.44).

Alison Brackenbury’s independently published ‘Village’ is available here (£9.99).

Nicola Chester’s most recent book ‘Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys through Time, Land and Community’ was September Book of the Month. Read an extract here, Melissa Harrison’s review here, or buy a copy here (£20.90). Paid subscribers can also read a bonus interview with Nicola.