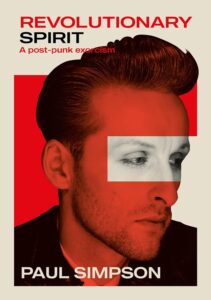

Roy Wilkinson reviews the remarkable memoir from Paul Simpson, Teardrop Explodes escapee, “Scouse Zelig” and obsessive art-conceptualist.

Do you like rock music? If you understand rock music as a place of grand theories and grand ambitions, a realm that might include the Teardrop Explodes, fist fights, unsettling incursions from Courtney Love, the deep yearning of the German concept of Sehnsucht and, indeed, remarkable rock music, then this book is for you.

Paul Simpson is the Scouse Zelig. In his teens he was in pre-fame bands with Ian McCulloch, Will Sergeant and Julian Cope – bands called things like Industrial Domestic and A Shallow Madness. He played keyboards for the nascent Teardrop Explodes, co-writing their debut single. Then he abruptly left – to pursue his own band ideal, leading to The Wild Swans, a band best known for the track after which this book is named. The ‘Revolutionary Spirit’ single was released on Bill Drummond’s Zoo label in 1982. Drummond says it’s the best ever single on Zoo, eclipsing the Teardrops and Echo And The Bunnymen. The ‘Revolutionary Spirit’ single wasn’t a hit, but The Wild Swans do eventually achieve a kind of commercial success – only, however, in the Philippines.

As Simpson tells it, The Wild Swans line-up is stolen from beneath him – and then resprayed and resold as The Lotus Eaters, who roar up the chart with their 1983 single ‘The First Picture Of You’. Simpson forms a new group, Care – as lead vocalist, alongside Ian Broudie. With Care’s debut album finished and a hit in the bag, Simpson flees the scene. There’s a pattern emerging – nervy exits bordering on a kind of fugue state. In 2005 Simpson is diagnosed with depression, while his rock disappearances were previewed in childhood. At around age nine he has what sounds like a mental breakdown. For two weeks, rather than attend school, every morning he walks six miles to loiter beneath a bridge on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. He’s there all day, unfed in the winter chill – the self-styled ‘coldest, loneliest child on Earth’.

If the Leeds-Liverpool iron-bridge sojourn suggests the lyrics of The Smiths’ ‘Still Ill’, Simpson’s book is much more self-aware than Morrissey’s autobiography – and, all in all, a far superior piece of writing. This book covers Simpson’s entire Earthly span to date, moving from a Merseyside childhood populated by a ‘groovy mum’ and a dad who served in World War II and whose fascination with military machines and biffing the Nazis is passed on to his son. A pre-teen Simpson attends a Blackpool package show featuring Roy Orbison, PP Arnold and The Small Faces. Child Paul is disappointed when the visages of the latter turn out to be ‘completely normal size’.

Among this book’s many highlights is its evocation of Liverpool on the cusp of the 1980s, when groups including Suicide, The Modern Lovers, The Cramps, Pere Ubu and a prototypical Joy Division all play at the venue Eric’s. Thus inspired, young men and women wander the Scouse metropolis, every waking moment filled with the holy imperatives of Forming A Band. Simpson is amazed when he first meets Ian McCulloch. The future Bunnymen frontman has milk-bottle-bottom glasses and ‘the fashion sense of a halibut’. But his sardonic wit is in place. “Good cheekbones,” he immediately tells Simpson. “But you’ll look like Peter Cushing when yer old.”

Simpson swaps the Teardrops for alternative employment at the Armadillo Tearooms, a caff known as the Armoured Dildo. Washing up and serving discounted tea to his pals, Simpson maybe seems at his happiest. A this stage anything can happen. Because it hasn’t yet not happened. Simpson is a style obsessive, pioneering various modes of second-hand chic. Plausibly, he claims to be post-punk trailblazer regarding the brutal olden-days short-back-and-sides that will become a signature hairstyle for the likes of A Certain Ratio and Bernard from New Order. Simpson swaps transitory employment for the dole and intermittent meals. Clothes and records are more important than food. In search of affordable grub, Simpson and Cope frequent a department store where the female staff take pity and purposefully damage pies so they can sell them on cheap to the emaciated post-punkers.

As Simpson says, ‘What I viewed as perfectionism in myself was interpreted by the industry as a self-destructive streak.’ So, it’s cheering to find the later stages of Revolutionary Spirit have both optimism and absurdity. There’s a remunerative return trip to the Philippines and thwarted plans for a conceptual heavy metal band called Three-Speed Crucifix Power Tool. Bill Drummond supplies a guest vocal for one of Simpson’s other bands, Skyray. As with the ‘Revolutionary Spirit’ single, Drummond has conspicuously praised this book. He’s not wrong. Paul’s sensitive, nuanced prose is manifest when, earlier in the book, Courtney Love moves unbidden into a flat Simpson is sharing with Bunnymen drummer Pete de Freitas. Simpson finds himself in an entry in Love’s diary, tragic-comically so.

This memoir suggests a strange social experiment – with Simpson as some kind of sleeper agent, living in deep cover as wildly wilful post-punk musician. And then emerging, 40 years later, as a writer of rare, magnesium-flare brilliance.

*

‘Revolutionary Spirit’ is out now and available here (£16.10), published by Jawbone Press. Read an extract from the book here.

Roy Wilkinson’s ‘Dark Lustre’ books are available here.